Timeline

1840’s

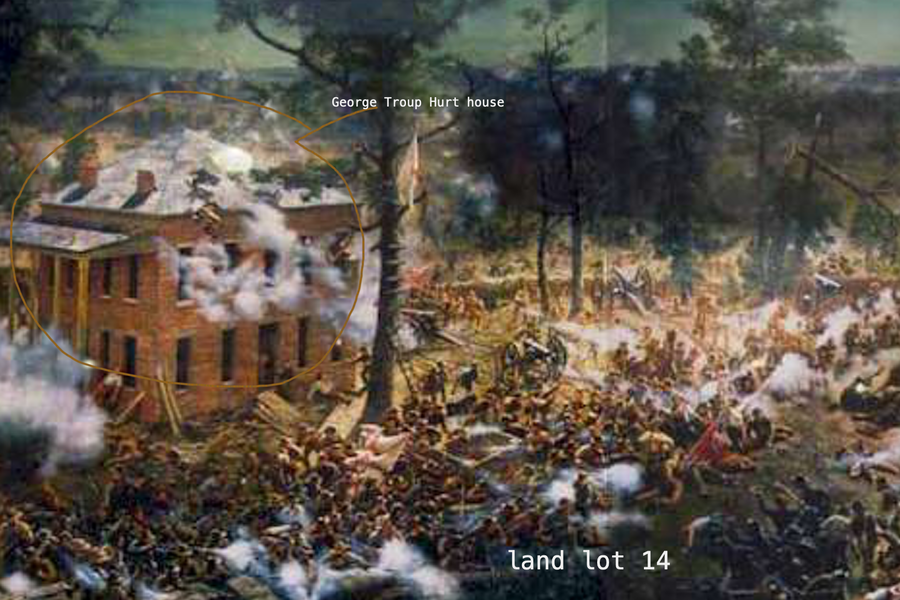

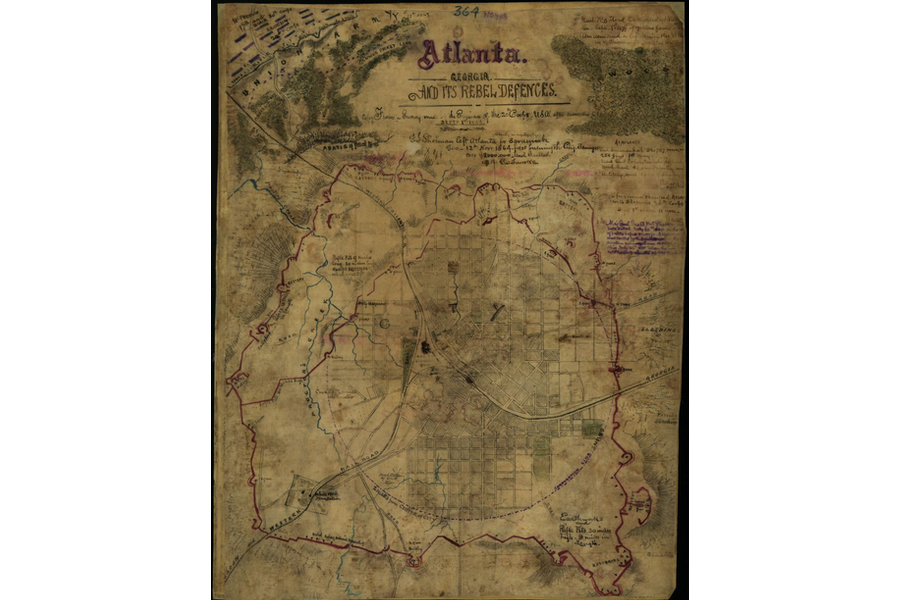

202.5 acres of land, encompassing what is now the southeast part of Poncey-Highland, the northern half of Inman Park, and the westside of the Little Five Points business district, are labeled as Land Lots 14 &15. They were part of the antebellum plantation of Mary Elizabeth Hurt & James Vickers Jones, who were early pioneers in the area.

1854-56

In 1854, the Joneses sell most of their property in Land Lot 14 (now mostly Inman Park) to her brother, George Troup Hurt.

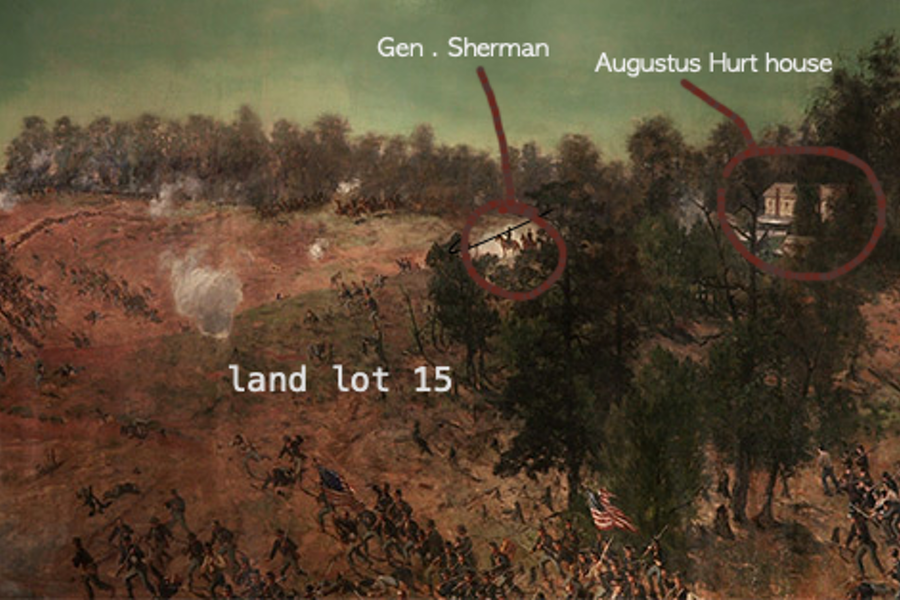

In 1856, all of Land Lot 15 (now part of Poncey-Highland, including the Carter Center) is sold to another brother, Augustus Fletcher Hurt.

About ThE Poncey-highland history project

This is a work in progress. We’re adding more to the timeline every day from hours of research done over the last year.

Do you have a story to tell? A correction to make? Want to help out? Please let us know by using this comment form:

1858

Augustus F. Hurt hires architect Henry B. Welton of Atlanta to build his 2-story home with a porch at the highest point in Land Lot 15, with a view across Clear Creek. This plantation home costs approximately $12,000, and it presumably sat on stone or brick footings. The home stood on the site of what is now the Carter Center, then listed as 176 Cleburne Avenue. Augustus Hurt lived there with his family and servants until tensions of the civil war caused them to move to a “safer area.” At the point when Union forces entered Atlanta, the Augustus F. Hurt house was being occupied by Thomas C. Howard, who operated the Clear Creek Distillery. Sometimes, the house is erroneously referred to as The Howard House.

1864

The home owned by Augustus Hurt is used by General Sherman in July of 1864 as his headquarters for The Battle of Atlanta, and for several weeks thereafter. From this location, Sherman was able to survey the battle, which spread between this house in Land Lot 15 and the house being built in Land Lot 14 for Augustus Hurt’s brother, George Troup Hurt. Both homes can be seen in the Cyclorama’s painting of the Battle of Atlanta. The body of General James B. McPherson, commander of the Union Army of Tennessee, rested here after his death during the fight. In the process of war, Sherman destroyed the A.F. Hurt home for firewood and shelter for his troops.

1865

John Armistead discovers a natural spring beneath his beech grove (under what is now Ponce City Market). In the late 1860s, Atlanta residents began visiting his Springs, two miles east of town as a way to supplement their residential water supply. A retired Atlanta physician, Dr. Henry L. Wilson, named the spot "Ponce de Leon Springs" based on his assertion that the water held rejuvenative properties. To meet rising demand, Armistead set up a residential water delivery service in late 1871.

Bathing Beauties at Ponce de Leon Springs 1890. Photo courtesy of Atlanta History Center

1866

The Atlanta Railroad Company is approved.

1870

Ponce de Leon Springs Amusement Park is built beside the spring.

Circle Swing, ca. 1910. Ponce de Leon Swing circa 1910, from the Healey Collection, courtesy the Atlanta-Fulton County Public Library. The sign below the circle swing reads: "Ponce de Leon is a private park under city police regulations. No disorderly characters tolerated. Colored persons admitted as servants only."

1871

Atlanta's population grew rapidly in the last decades of the nineteenth century, from almost 22,000 in 1871 to nearly 65,000 in 1888. Local businessmen set out to build additional transportation networks, and between 1872 and 1888, eleven more street railroads were chartered. With growing demand and competition, some entrepreneurs looked towards emerging technologies to distinguish their railroads. The Metropolitan Street Railroad Company experimented with dummy steam engines in the mid-1880’s, but residential complaints about smoke and the dearth of experienced engineers created more problems than profit.

1872

Augustus Hurt subdivides his property in Land Lot 15 near the busy intersection of Turnpike Rd. (Euclid and Austin) and County Line Rd. (Moreland).

1874

The Atlanta Railway’s Ponce de Leon line of horse drawn streetcars is extended to the Springs with service every 15 minutes from 5:30am-10:00pm for a fare of 10 cents. The growing traffic from Atlanta to the Springs drew the attention of Richard Peters, co-founder of the Atlanta Street Railroad Company. Looking to profit from the city's latest hot spot, the streetcar company extended its Peachtree Street Line east to Armistead's property in 1874, along what is now Ponce de Leon Avenue. The extension required the construction of a two-hundred-fifty-foot-long trestle over Clear Creek. The railroad's investment soon paid off as the popular line took Atlantans by horse-drawn trolley to the Springs for a ten-cent fare.

1879

Copenhill Land Co. begins platting lots for a proposed subdivision.

1886

The temptation to capitalize on the Springs led Armistead to begin charging five cents a person to drink the water in May, 1886. Enraged, E.C. Peters, son of Richard Peters and Atlanta Street Railroad's general superintendent, launched a campaign against Armistead for control of the Springs. Peters told the Atlanta Constitution that the new fee infringed on an 1874 agreement between the railway company and Armistead. While the railway held no control over the Springs themselves, Peters saw the site as an lucrative investment. If patrons balked at the five-cent fee, Atlanta Street Railroad lost their passengers and the income from the Ponce de Leon Line.

1888

Copenhill Land Company incorporates to develop Copenhill Park, Atlanta’s second street car suburb, which encompassed most of the land in Land Lot 15 that belonged to Augustus Hurt and the southern part of Land Lot 16. The streetcar lay: northwest of what is now Sinclair Ave, and included Highland Ave. from Elizabeth to North Avenue, east of the Southern Railroad (now the Beltline), and south of Williams Mill Rd., a small portion of which still exists. The rest ran roughly along the northern edge of the Carter Center.

Copenhill gets its name from its founders: Frank Coker, H. Pendleton, and Lodewick Johnson Hill. Partners in the company were brothers Oscar Davis as President, and Charles A. Davis as treasurer, and LJ Hill (President of 9 Mile Circle Rail). Copenhill was a “garden suburb” and the centerpiece was Madeira Park, which was created out of a natural ravine near the center of the development. The plan incorporated old country roads into a system of curvilinear streets defined by small circular or triangular parks. Other open spaces were also included in the original design, most notably the small lake near the intersection of Layal (now Colquitt) Avenue and Highland Avenue, which was fed by a small branch that formed part of the headwaters of Clear Creek. The Copenhill developers cooperated with the Inman Park developers to insure both suburbs were finished to the greatest advantage of each other.

1889

In 1889 the first electric streetcar runs on Atlanta streets.

1890

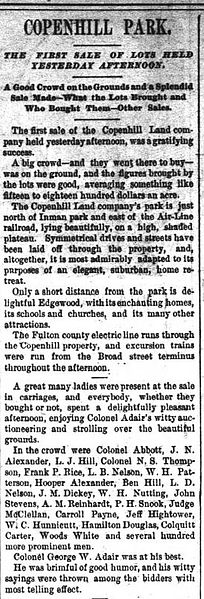

In April of 1890, Col. George Adair auctions off the first lots of the new subdivision Copenhill Park. The area was attractive, among other reasons for its accessibility to the Nine-Mile Circle streetcar line along Ponce de Leon Ave, though streetcar service was later added on Highland Ave.

1908

The areas of Copenhill and Inman Park are annexed into the city of Atlanta as the Ninth Ward.

In the early 1900’s, the home of Albigence Lamar Waldo and family is built on the site of the Augustus Hurt house (what is now the Carter Center), and remains until approximately 1930 when it is removed.

Beginning of a building boom and bungalow craze in Atlanta.

1910

Dr. George Frederick Payne, a co-founder and key faculty member of the Atlanta College of Pharmacy, and real estate developer William E. Worley, begin buying land and developing the now historic Bonaventure-Somerset area of current Poncey-Highland. The Payne-Grifffith House (NRHP, and listed as The Bonaventure) is built in 1910, as Dr. Payne’s residence.

1911

The Highland School (now Highland School Lofts) is built on land purchased by the City of Atlanta from the Copenhill Land Co., which set aside 5 lots for the purposed of having a school located within the Copenhill subdivision. It served the nearby neighborhoods of Druid Hills and Highland Park (in what is now Virginia Highland) in addition to the Copenhill neighborhood.

1914

Ford Motor Company opens its manufacturing plant. The 4-story, 150,000 square foot building was designed by Ford’s in-house architect, John Graham. Ford established a combined assembly, sales, service and administration facility on Ponce de Leon Avenue, selling a peak of 22,000 vehicles per year. The assembly plant produced Model T’s, Model A’s and V-8’s.

1924

The Bonaventure Arms Apartments (now Hotel Clermont), an upscale apartment building, opens in 1924. Designed by Atlanta architect Raymond C. Snow, it is a fine example of the apartment buildings that were springing up along Ponce de Leon Avenue to provide housing along the popular public transportation corridor.

1928

Subdivisions in what is now Poncey-Highland are largely complete.

Druid Hills Baptist Church (still existing) and The Southern Christian Home (demolished) for orphans are built in 1928.

1939

The Western Electric Company builds its telephone factory. It is an excellent representative example of the Streamline Moderne style of architecture in Atlanta. The building is designed by Walter R. Kattelle, an in-house architect for the Western Electric Company.

The art deco Plaza Theatre and Briarcliff shopping Plaza are finished by Architect George Howell Bond (1891-1952). A prominent architectural historian said it “remains Atlanta’s best surviving neighborhood Art Deco theater.” Atlanta’s first theater and shopping center with off-street parking, the retail complex was the idea of developer John Candler, son of Asa Griggs Candler, Jr., and grandson of Coca-Cola magnate Asa Griggs Candler, Sr. A response to changing patterns of growth in Atlanta, it was conceived to serve the residents of the Briarcliff luxury apartment building across Ponce de Leon Ave. and the nearby residential suburbs, including Druid Hills. The Majestic Restaurant and Blick’s Bowling Palace were the first tenants. By 1941, city directories show that 12 of the available 14 storefronts were occupied. The Briarcliff Plaza is now a City of Atlanta Landmark District and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

1940’s

Steady growth begins to slow, and the automobile starts to edge out the streetcar as the preferred mode of transport. Cars allow a new kind of freedom to spread out, and suburbs further from the city center draw urbanites away from in-town living. Public transportation around the city devolves into something used mostly by those who cannot afford a car. Some call it White Flight, where the affluent whites leave the convenience of the diverse city behind, in exchange for homogenous neighborhoods farther away. Once the people with money leave, the intown neighborhoods begin to decline. Ours was one such neighborhood, and in 1946, the city starts planning for expressway use through Poncey Highland and adjacent neighborhoods.

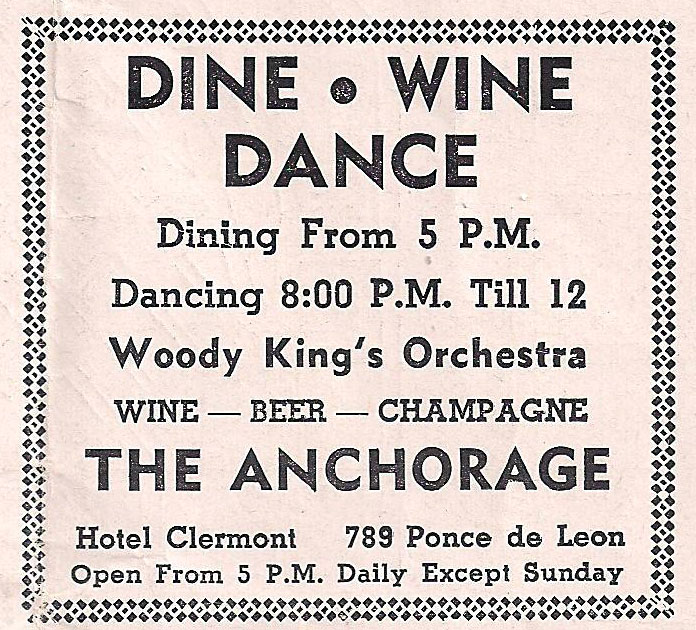

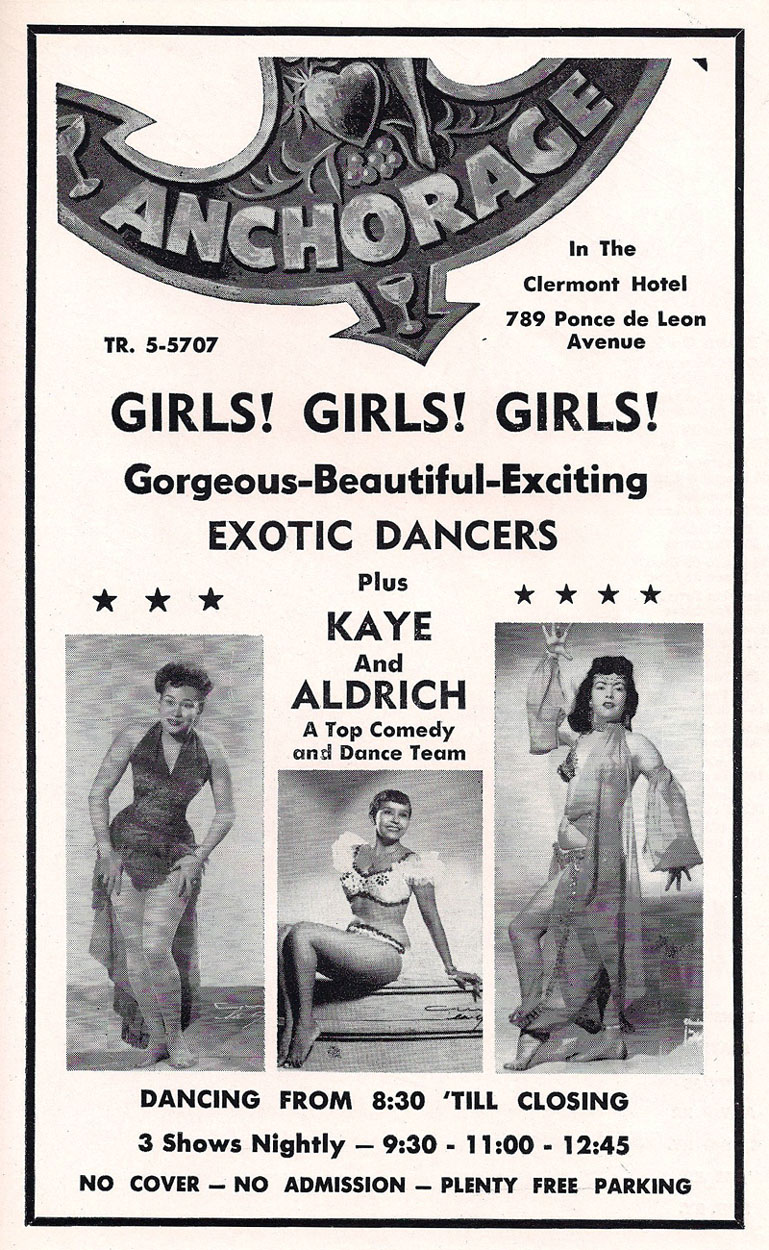

In the mid-1940’s a night club called the Anchorage Club opens in the basement (terrace level, it was originally called), and offers music and dancing. By the 50’s and 60’s, the club is offering up “exotic dancers” and “girls, girls, girls”. Now called the Clermont Lounge, it’s Atlanta’s oldest operating strip club, featuring dancers who have been on the stage for decades.

1956

Manuel’s Tavern opens.

1960’s-1980’s

In 1961 the state buys land to make way for the interchange of the I-485 freeway (which is never built), and in the process, historic Copenhill is razed, and over 500 homes, churches, businesses, and civil war sites are demolished throughout Copenhill, Inman Park, Candler Park, and Old Fourth Ward, including a large part of what is now Poncey-Highland. Illicit drug and prostitution markets move in to Poncey Highland and the surrounding neighborhoods. The Plaza Theatre deteriorates, showcasing live burlesque shows and X-rated pornos. Plaza Drugs, ironically stands in the Briarcliff Shopping Plaza near the intersection of Ponce and Highland, and seems to iconically represent what is happening in our neighborhood. Vacant homes give way to sex workers renting rooms by the hour, drunks and homeless folks take up residence in alleys, but throughout this period, our neighborhood seems to develop a “live and let live” attitude- one of tolerance for those who frequented the bars, clubs, and restaurants and “do time” among the residents of the area.

In George Mitchell’s book simply titled Ponce de Leon, he compiles interviews of cooks, prostitutes, pimps, winos, strippers, business owners, waitresses and other folks who live or work along our stretch of Ponce in the early 80’s. A common thread, not unique to just one person interviewed, but running throughout the book, is a universal sense of acceptance in our neighborhood. Karl Kabboushy, a Syrian immigrant who was manager of the soda fountain at Plaza Drugs said it well;

“I don’t think you could find a place like this in the whole world. The most unique thing about it was its customers. They were different, they were from all levels of society. There wasn’t any monopoly by any single part of society on the place. It was catering to different kinds of people. The people who came in here were very, very nice people. It is the most misunderstood place, as far as the media goes, that I know of. They always write about drunks and winos and all that. There is that, yes. There’s the other side of it too. The nice, respectable people, the church-going people, that come down here, too. This is a public place and you get people from all walks of life to come in here.

That is, I think, the most unique thing…”

1971

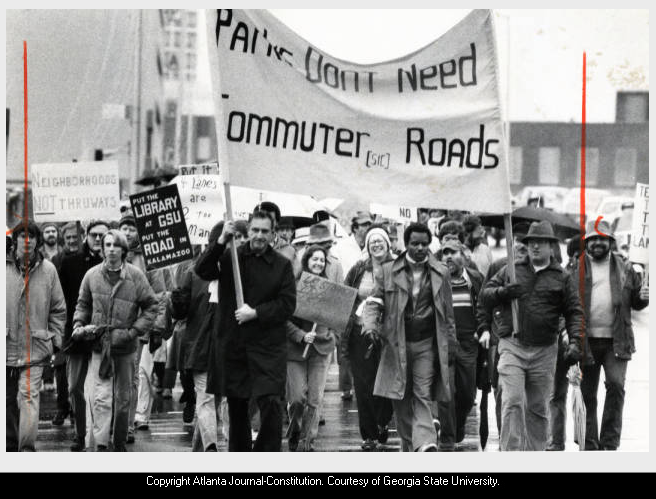

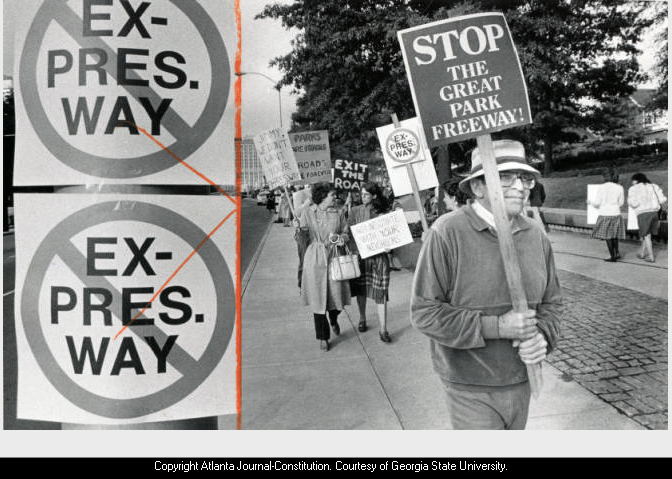

Strong neighborhood opposition convinces a judge to suspend construction on I-485 until an environmental study is completed. Groups of neighbors organize to protest and protect against I-485 development and further damage to Poncey-Highland and surrounding historic neighborhoods.

1974

Mayor Maynard Jackson designates Neighborhood Planning Units (NPU) as citizen advisory councils to make recommendations to the Mayor and City Council on zoning, land use, and other planning issues. The Poncey-Highland Neighborhood Association is formed (PHNA)

Atlanta architect- developer John C. Portman Jr. creates a master plan for The Great Park, with a $157 million complex on 219 acres. It was submitted to Gov. Busbee as a suggestion of what would occupy the land in the wake of the freeway clearing.

1976

The Atlanta Film Festival begins at The Plaza Theatre.

1979

Ponce de Leon, Atlanta’s all-night street represents the pulse of Poncey Highland during this decade.

1981

Former President Jimmy Carter proposes locating his library and parkway to surround it, in the plan for The Great Park (now Freedom Park).

1982

CAUTION (now Freedom Park Conservancy) and Road Busters is formed by a group of neighbors and activists to oppose the road. Road Busters, an informal collective, participates in nonviolent civil actions while CAUTION Inc (Citizens Against Unnecessary Thoroughfares in Older Neighborhoods) leads the legal battle against the DOT roads.

1983

Atlanta Businessman Robert Griffith begins restoration on The Plaza Theatre in an effort to restore the block to its former glory.

The Environmental Impact Study of neighborhoods surrounding I-485 is completed. Opposition to Freedom Parkway continues.

1984

Ford Factory Assembly Plant is converted to apartment lofts, and renamed Ford Factory Lofts. The building receives a listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

1986

The Carter Presidential Library and The Carter Center are dedicated in October, 1986

1986-1994

Conflicts, lawsuits, activism, and opposition to construction of the road continue until 1992, when GADOT, CAUTION and the City of Atlanta enters a court ordered mediation with Judge Seliger to resolve the dispute over what is to be done with the land around the Carter Center. The settlement results in 200+ acres of land being dedicated to park use as Atlanta’s Public Art Park (Freedom Park), and a parkway (Freedom Parkway). Construction on the parkway begins shortly thereafter, and neighborhood groups, park designers and city planners work on a design for Freedom Park, which would surround Freedom Parkway.

1995

Western Electric Company building is converted to Telephone Factory lofts by developers Rhodes and David Perdue. They apply for bond financing from the Atlanta Development Authority (ADA), the city's development arm. As a condition of providing the financing, the ADA requires, as part of an affordable housing program, that one-fifth of the units be made available for people earning 50% of the area median income, ($25,000 per year) or less. The lofts open in 1996, and for fifteen years through 2011, units are offered as live/work space to artists, writers and designers at inexpensive prices under the program. In 2011, the units ware transitioned to market rates. Upon conclusion of leases, occupants are asked to sign new contracts at much higher market rates if they wish to stay.

1996

Freedom Parkway and the first phase of Freedom Park open just before The Olympics take place in Atlanta.

1997

The Bridge, a sculpture by Thornton Dial is erected in Freedom Park on the corner of Freedom Parkway and Ponce de Leon. It portrays “congressman John Lewis’ lifelong quest for civil and human rights” and the community’s “valiant efforts to stop the road and preserve intown neighborhoods”. The sculpture is dedicated to Rep. Lewis in 2005 through the leadership of members of CAUTION, Freedom Park Conservancy, and the City of Atlanta’s Office of Cultural Affairs.

2000

Freedom Park is completed and officially dedicated, and in 2007 it receives a designation as Atlanta’s Public Art Park by Atlanta City Council.

The Park now connects the many revived in-town neighborhoods whose residents fought to stop the roads, the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site, and the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum. Miles of trails built by PATH Foundation wind through the Park, and thousands of people use the park every week for exercise and relaxation.

2003

The Highland Building, 675 Seminole, reopens as office condos after an adaptive reuse effort.

PHNA applies for Livable Communities Grant to fund the development of a master plan.

2004

The Highland School is designated as a City of Atlanta Landmark Building Site.

2009

The Children’s Playground opens in Freedom Park, as Atlanta’s first community-built, eco friendly playground, and a community garden is established in the park.

With urging from Kwanza Hall, then the city council representative for District 2, Poncey-Highland begins a community-based effort to create a master plan for the neighborhood.

2010

The Poncey-Highland Master Plan is adopted by the City of Atlanta.

The population in Poncey Highland is 2,133.

2012

The first 2-mile stretch of The Atlanta Beltline Eastside Trail opens along the western border of Poncey-Highland.

2013

The Plaza Theatre is sold and undergoes extensive renovations, including the addition of a full-service bar.

2014

Ponce City Market opens as a mixed-use development in the old Sears and Roebuck Building along the Eastside Beltline trail. It earns a LEED Core & Shell certification at the Gold level for its two-million-square-foot, 1920’s era adaptive reuse space in an urban and transit friendly location. It is still the largest brick building in the south.

2015

Manuel’s Tavern, an Atlanta establishment since 1956, is sold and thoughtfully restored. The original owners, the Maloof family, maintain ownership of the business.

2017

The Briarcliff Shopping Plaza complex is sold for $18 million, and the Poncey Highland neighborhood requests historic designation for it, in order to protect its rich history as an iconic building in our neighborhood. With support of the new owners, The City of Atlanta Briarcliff Plaza Landmark District is created, and extensive restoration and improvements begin, as new tenants move in.

The Plaza Theatre business, which operates in the Briarcliff Plaza complex is sold to Christopher Escobar, executive director of The Atlanta Film Society.

The Kroger Grocery store located in the parking lot beside Ford Factory lofts closes. This location opened shortly after 1986, when low-interest government loans were used to convert the adjacent and former Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant into lofts and commercial spaces. This particular store is known by locals as “murder Kroger” due to murders and suspicious deaths that took place in its parking lot in 1991, 2002, 2012, and 2015. It is set to reopen in 2019 after extensive renovations as part of the 725 Ponce mixed-use complex.

2018

The Virginia Court Apartment building, located at 881 Ponce de Leon Ave is designated as a City of Atlanta Landmark Building Site, as owners request permits to demolish it.

The Hotel Clermont (former Bonaventure Arms Apartments, and Clermont Motor Hotel) reopens after an extensive adaptive reuse project. The Clermont Lounge which has been operating in the basement since the 60’s is also restored, and retains its pre-renovation appearance.

2019

The Bonaventure-Somerset Historic District is established, in a residential section of Poncey-Highland originally called Ponce de Leon Heights, along the thriving Atlanta BeltLine Eastside Trail.

2020+

What will history say about you?